Fifty weeks of jazz

Right—the holidays are over, the Christmas tree is fuel for the fire, and the worst of the NYE champagne bottle shards have been swept up; it's time to get serious. As in, resolutions.

Update, 2025-10-30: if you're just popping in for the first time, I recommend you skip past the first few entries; like most series, this one took a little time to find its footing. I'd say it starts to pick up around week 12; week 15, week 28, week 30, week 31, and week 39 are among my favourites.

Over the past few months I've been trying to listen to more jazz. I can't quite remember what started this whole project, but now I won't rest until I've achieved my own transcendental jazz trance.

As it so happens, while checking out the local flea market recently I chanced upon some very relevant box sets, comprising some fifty classic jazz albums.

So here's the plan: at one album per week, that gives me about a year of autodidactic jazz education, plus a buffer at the end for some self-reflection. I don't have a textbook or any other proper guide; I'm just going to listen to the albums, binge some Wikipedia pages, and see where that gets me in a year.

Fair warning: this post is just going to be me brain-dumping my uneducated, undiscerning thoughts on these albums. I don't imagine it will be entertaining or useful in any way for literally anybody else, but hey, you're the one reading it. If, for some misguided reason you do want to follow along, there's a dedicated feed for just this project in addition to the overall blog feed, as well as a separate section of the site.

Table of contents

- Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy

- Sarah Vaughan in Hi‐Fi

- The Jazz Messengers

- Lady in Satin

- Kind of Blue

- Time Out

- First Time! The Count Meets the Duke

- Parole E Musica

- Tijuana Moods

- Chet Is Back!

- Monk's Dream

- Sonny Meets Hawk!

- At Newport '63

- Two of a Mind

- Together Again!

- It's Uptown

- Nina Simone Sings the Blues

- Piano Starts Here

- Concert by the Sea

- Head Hunters

- The Best of Two Worlds

- Jaco Pastorius

- Heavy Weather

- Marsalis Standard Time, Volume 1

- Bird: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack

- Ellington Uptown

- Jazz Goes to College

- Satch Plays Fats: A Tribute to the Immortal Fats Waller

- ’Round About Midnight

- The Sound of Jazz

- Mingus Ah Um

- Desmond Blue

- The Bridge

- The Electrifying Aretha Franklin

- Silk & Soul

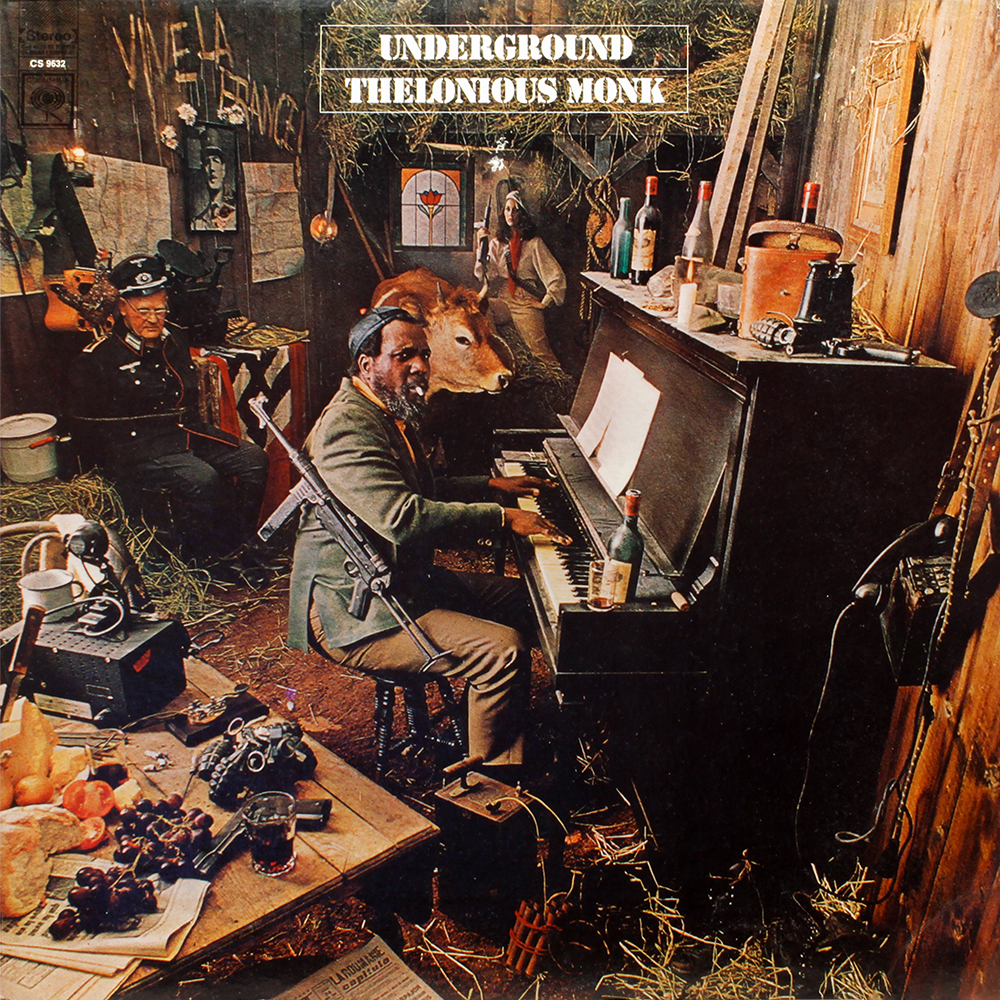

- Underground

- Straight Life

- Beyond the Blue Horizon

- Birds of Fire

- The Beginning and the End

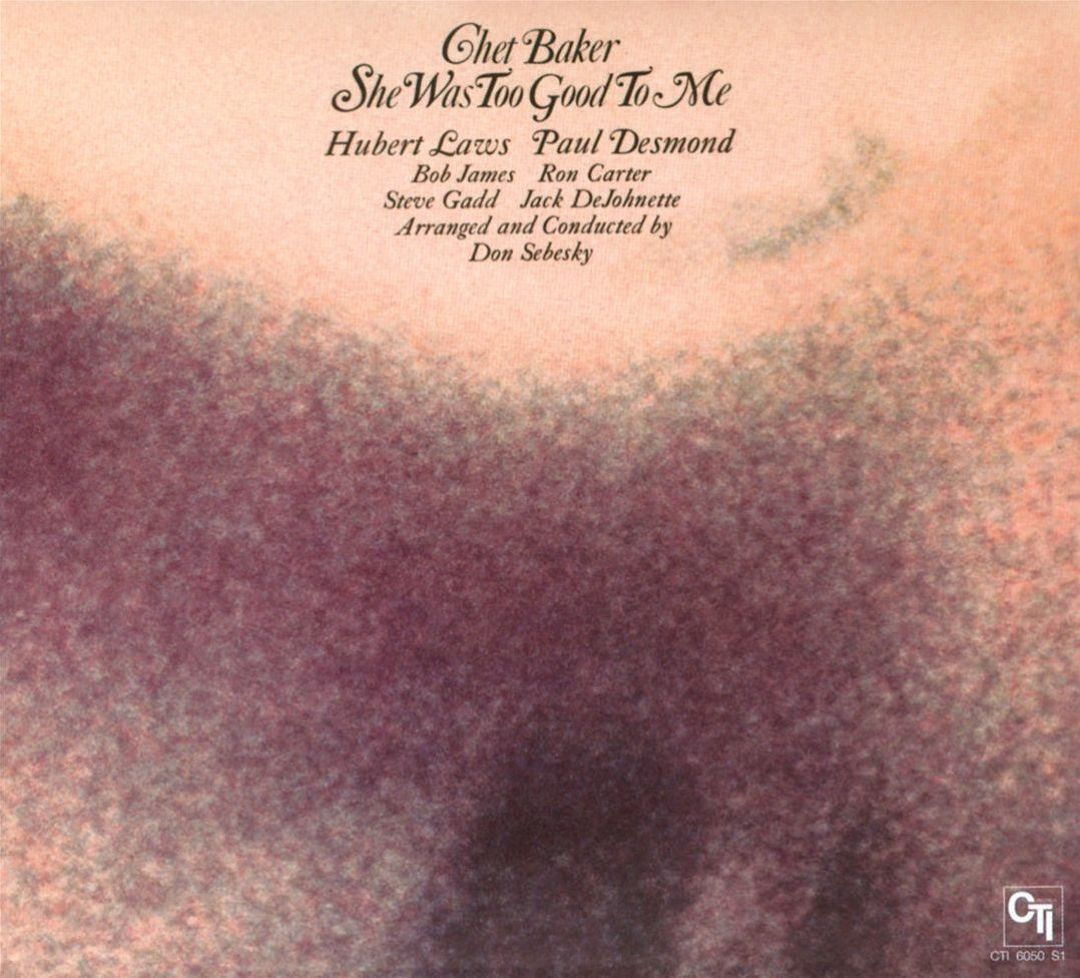

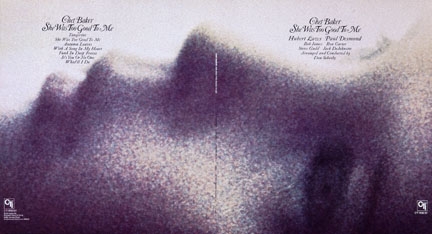

- She Was Too Good to Me

- Carnegie Hall Concert

- Native Dancer

- Concierto

- Romantic Warrior

- School Days

- 8:30

- Round Midnight: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack

- Carmen Sings Monk

- Standard Time, Vol. 3: The Resolution of Romance

Week 1: Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy

Not really knowing anything about these box sets in advance, I embarked on this project with some trepidation that I had signed myself up for fifty weeks of crap. By the end of this album's first track, I was a believer.

The top-notch musicianship and Satchmo's1 trademark gravelly crooning are already reason enough to listen, but I can't emphasize enough how much fun this album is: the frequent banter between Louis and Velma Middleton is charming, and the whole thing is joyous and downright raucous throughout. I mean, just listen to this laugh:

One thing I don't understand: W. C. Handy was the "Father of the Blues," and most of the songs here have "blues" in the title—obviously there's lots of shared heritage between jazz and blues, but where exactly does that dividing line lie? And what is this exactly?

Favourite track: St. Louis Blues

Week 2: Sarah Vaughan in Hi‐Fi

This one is a slower burn for me: obviously Sarah Vaughan is an incredibly talented vocalist, but this doesn't quite get my blood pumping like the last album; sometimes her melodies go a little too all over the place for my taste. That said, I'd gladly put this on for a nice romantic dinner (skip "Mean to Me" in that case, though).

Also, apparently Miles Davis is playing the trumpet for most of these tracks? We'll get back to him soon enough…

Favourite track: Nice Work If You Can Get It

Week 3: The Jazz Messengers

After Ms. Vaughan's lovely but somewhat sedate tunes, I was hoping for this week to bring a little more energy, and The Jazz Messengers definitely delivered on that front. Wikipedia tells me we're in hard bop territory now, and it's not hard to hear why it might've earned that moniker.

Art Blakey is undeniably a monster on the drums, but some of his solos end up sounding a little… samey to me? Take the first big solo from Infra-Rae: it starts to get repetitive for me in a way that I've never felt when listening to say, Neil Peart. Listen for yourself and see if you agree:

Not too much more to say on this one, other than that I'm glad to have some high-tempo, vocal-free jazz—good music for when you really need to get something done. Oh, and "Carol's Interlude" on this album really reminds me of "Epistrohpy" from another Monk/Coltrane album I have.

Favourite track: Hank's Symphony

Week 4: Lady in Satin

Given that the primary feature here is a solo female vocalist—Billie Holiday—I couldn't help but compare this album to the earlier Sarah Vaughan album. I prefer this one: the lush orchestral backing really helps create a sweeping, dramatic sense of romance, as opposed to Vaughan's lighter, airier mood.

Immediately, one can hear some fragility and rasp in Holiday's voice; she comes across as much more "mature" than Vaughan to my ears. What I hadn't realized was the sad explanation: at the time of the recording, Holiday was in poor health, after having weathered decades of damage from alcohol, hard drugs, and abusive relationships. She recorded this album in February 1958 and passed away barely 18 months later. The critical consensus seems to be that the album packs a huge emotional punch, but that Holiday had lost some of her range and force by this point—I'd like to return to her earlier work and compare for myself.

I suspect this album will also hold a special place in my heart owing to the circumstances of my first listen: not wanting to miss a week, I had copied this album to my phone in advance of a trip to the Netherlands; I listened to it together with my wife on the train as we watched the Dutch countryside go by.

Two miscellaneous closing thoughts:

- It's a dang shame that she never had a chance to sing a Bond theme (and not only because that would up the Billie–Bond count to two).

- Thanks to Wikipedia, I learned that there's a crater on Venus named after her.

Favourite track: For Heaven's Sake

Week 5: Kind of Blue

We're into the heavy hitters now—this is one of the few jazz albums I picked up prior to this experiment, based on its universal praise. What is there for me to say that hasn't already been said? It's Kind of Blue—if any album is jazz, it's this one.

From what I've been able to gather online, Kind of Blue is notable for pioneering modal jazz (in response to hard bop). My limited understanding is that in hard bop, melodies were largely driven by quick chord progressions: soloists displayed their incredible virtuosity by continually adapting to the rapidly shifting tonal centre dictated by the chord changes. In contrast, modal jazz uses very few, slow-moving chords—giving soloists more latitude to develop their melodies without being constrained by the strictures of the chord progression. (As for what exactly musical "modes" are and what their significance is, I still don't have a clear understanding.)

I'm sure I'll be listening to and learning from this one for many years to come, along with the rest of the world.

Favourite track: So What

Week 6: Time Out

This album was an immediate revelation for me. I've listened to some great stuff already, but Time Out had me hooked from the first few bars—the opening rhythm of Blue Rondo à la Turk is now permanently tattooed on my brain. Perhaps that's no coincidence; Time Out's primary innovation is its usage of time signatures that were previously uncommon in jazz (e.g., 9 8 in Blue Rondo à la Turk; 5 4 in Take Five). If, like me, you're struggling to understand the nuances of 9 8 rhythm, here's a helpful explanatory video from Wikipedia:

Got it? Good.

Another thing that stood out to me was how… classical this album sounds? Even on my first listen, something here struck me as familiar in a way I hadn't experienced with the earlier albums.

One more embed before we go: Canadian film animator Steven Woloshen produced a short film set to Take Five that I think is pretty neat:

Favourite track: Blue Rondo à la Turk

Week 7: First Time! The Count Meets the Duke

As previously mentioned, I had listened to a grand total of three jazz albums before setting out on this expedition. We've already encountered Kind of Blue; one of the other two was Side by Side—Side by Side was mostly a Johnny Hodges album, but they stamped his better-known bandleader Ellington's mug on the cover, presumably to juice the sales.

I bring all of this up because this week's album features some of the same suspects: Ellington has gathered together his big band (Hodges included), but they're not alone: Count Basie—another big band luminary—is on set with his crew, and out to wage Big Band "Battle Royal" (sic)! The stereo mix is intended to capture the conflict: Basie's group is heard on left channel, while Ellington's is on the right.2 To my undiscerning ear, the result sounds as cooperative as it does antagonistic, but that doesn't stop it from being a blast through and through. At peak moments, the brass can get a little screechy; I don't think it's ever over the top but my wife is not on board with it. (E.g., listen to the climax of Battle Royal—it's on the verge of cacophony, but I think it remains on the "impassioned finale" side of the line.)

I've bandied about "big band" above with any proper explanation, so I suppose I ought to fill in some of those details: big band is exactly what it sounds like—a musical ensemble for jazz that consists of at least ten (and often 17 or more) musicians (usually divided into saxophones, trumpets, trombones, and rhythm). Compared to earlier jazz ensembles (which typically comprised 4–5 musicians), big bands were obviously larger, but also had a greater focus on written compositions (owing to the increased difficulty of coordinating solos across a much bigger group). Big bands reached peak popularity in the late 1930s/early 1940s alongside "swing," the subgenre of jazz they usually played. Swing was very popular at dance halls; as you might guess from the name, it features a "swinging" rhythm (usually by accenting the second and fourth beats). Both Duke Ellington and Count Basie were both highly regarded big band leaders who shaped the development of swing (Ellington in particular was also a prolific composer and arranger).

tl;dr:

- Big band

- Jazz group of at least ten musicians (probably more).

- Swing

- Subgenre of jazz with a strong emphasis on a "swinging" rhythm; frequently played at dance halls.

Favourite track: Wild Man (aka Wild Man Moore)3

Week 8: Parole E Musica

Eight weeks in, and we've arrived at a dubious honour: this is the first album where the top-billed performer (Helen Merrill in this case) is still alive—as I write this in February 2025, she's a sprightly 95 years old according to Wikipedia. Perhaps more excitingly, we've also got our first duplicate track: we first heard "You Don't Know What Love Is" in week 4 (I give the edge to Merrill).

This album has an interesting gimmick. For each "song," there's two tracks: the first is a spoken word version of the song's lyrics in Italian; the second is the real song (with Merrill singing in English). Is it completely unnecessary and self-indulgent? Yes. Do I love it, and does it make me pretend I'm living on the Amalfi Coast in Ripley? Also yes.

Also, this is the third album to feature a lovely leading lady, and I have a confession to make: while there's no denying the sublimity of Merrill's singing, it's pretty clear to me by now that this isn't what I want out of my jazz—I'd almost always sooner reach for any of the instrumental albums we've heard, or Armstrong's bombastic vocals.

One final bit of trivia for the week: this might be the first you've heard of Helen Merrill, but you surely know one of her son's songs: he wrote the original version of "I Love Rock 'n' Roll."

Favourite track: Why Don't You Do It Right

Week 9: Tijuana Moods

Charles Mingus was another one of those "big names" from the jazz world that I recognized, but had never actually listened to until this week. Tijuana Moods sounds quite different than anything else we've heard so far; I'd describe it as more assertive and even a bit combative at times (though smooth elsewhere; e.g., on "Flamingo"). This certainly isn't "easy listening;" compared to the other albums it feels less eager to please the listener and more experimental—maybe it's fair to call it a concept album? As you might've guessed, the album was inspired by Mingus' time in Tijuana; throughout the album, even my ignorant ears can clearly discern the Latin beats and motifs getting the blood pumping as the jazz takes off.

But the track that's stuck with me the most isn't even from the original release of the album. "A Colloquial Dream (Scenes in the City)" was only added on some later CD releases: it's nearly 11 minutes long and merges jazz with spoken-word poetry; it features a down-on-his luck narrator recounting his love for jazz and his struggles living in Harlem. At first, I didn't like it, and I wasn't convinced it was likeable by anyone—a fun novelty, sure, but is this still even music? But after listening to the album all week long, propinquity did its thing, and that narrator now lives rent-free in my head (a good development for him given his situation with the landlady). This isn't the kind of song you can blast at the gym or put on your party playlist, but if you're in a ruminative mood—possibly with a dram of whisky in hand—there's a real depth of soul here.

Now catch this… DIG!

Favourite track: A Colloquial Dream (Scenes in the City)

Week 10: Chet Is Back!

Ooh, this sounds pretty different to me than what we've heard so far. I think that's mostly due to the appearance of electric guitar in a few tracks and more prominent bass throughout—it strikes me as more "modern" overall? The song that most captured my attention was "Ballata in forma di blues," written for the album by Amedeo Tommasi (who also plays piano on the album); something about that starting chord progression had me completely transfixed. Interestingly, almost none of the other songs on the album were original compositions. They're almost exclusively covers, including a Thelonious Monk track (remember that name) and that perennial favourite, Over the Rainbow.

After eight instrumental tracks, I wasn't expecting the vocals on the last four (all sung by Baker himself). There's a good reason for that—those four tracks weren't on the original album release; they were a series of "orchestral pop tracks" that Baker later recorded with Ennio Morricone. (Yes, that Ennio Morricone.) Regardless, they've got a calm charm of their own that complements the more upbeat earlier tracks. I'm glad they were added for this CD reissue.

As for Chet Baker the man, he seems to have been the poster boy for everything your high school's anti-drug program said would happen—with his boyish good looks and multifold musical talents, surely the world was young Chet's oyster! Unfortunately—like many of his contemporaneous jazzmen—Chet developed a heroin addiction early in his career and spent the rest of his life in and out of jail. He died at age 58 after apparently falling out of a hotel window while high.

As if that wasn't sad enough, Wikipedia's biography of Chet includes the sentence "Baker was an irresponsible and distant father," with a footnote. Dear reader, I will be a father myself soon, and while I am sure I will make more than my own fair share of mistakes, I'm hoping not to foul it up to the point that it's citation-worthy.

One more obligatory random connection. Remember when I said that listening to Parole E Musica made me feel like I was in Ripley? Turns out I was a couple of weeks early—in the 1999 movie The Talented Mr. Ripley (based on the same source material as the 2024 miniseries), Matt Damon impersonates a Chet Baker recording.

Favourite track: Ballata in forma di blues

Week 11: Monk's Dream

Moms didn't dig [jazz], she just didn't go for it

Bird, Miles, and Max… she couldn't see it

Morning, afternoon, night, or anytime

That is, until I played her some Monk one night, late

I played her some Monk!

—Thelonious, that is

And now Mom spends many of her nights in Tunisia

—"A Colloquial Dream (Scenes in the City)"

I suppose you can tell that Thelonious Monk is a big name given that I've already alluded to him three times so far before actually getting to one of his own albums.

In retrospect, I can see that I came to this album with misplaced expectations. Knowing how revered Monk is and that this is one of his best-known albums, I was expecting something more avant-garde—something challenging and foreign; something that had moved jazz as a whole forward. Instead it's a… very fun and dare I say approachable listen? If someone wanted to dip their toes into jazz, this seems like a pretty reasonable recommendation to me.

Everything that I've read about Monk mentions his idiosyncratic approach to piano—his percussive attacks on the keys, "angular" melodies, and emphatic use of dissonance and silence. I'm still too much of a neophyte to discern those in any sophisticated way; I can hear the dissonance come through in places (particularly in "Body and Soul"), but I doubt I could pass a blind "is it Monk?" test.

Perhaps the above makes it sound like I'm down on the album, which isn't the case. There's a lot of fun and whimsy here; I particularly like the scratchy sax in "Bright Mississippi" and the main jaunty melodic line it features. "Bye-Ya" and "Sweet and Lovely" also stand out because I know them from an earlier album (not featured in our 50-week journey)—in "Sweet and Lovely" I prefer the halting ritardando ending on Monk's Dream to the chromatic (?) flourishes on the other album.

But overall, I'm leaving this week with a renewed appreciation for Tijuana Moods—I think that's closer to what I wanted Monk's Dream to be. Maybe by the end of this project I'll be able to better appreciate Monk's genius in its own right.

Favourite track: Bright Mississippi4

Week 12: Sonny Meets Hawk!

Ah, the saxophone: I'm sure we can all agree, objectively one of the best instruments. And this week we're treated to a sax masterclass: as the back cover helpfully explains, we've got Sonny Rollins ("the 'boss' of modern tenor sax") on the left channel, and Coleman Hawkins ("the father of jazz saxophone") on the right.5 These are indisputably two masters of the instrument, live in improvisational conversation with one another, and what a conversation it is.

But first! Since we're on the topic of the saxophone, there's something I positively have to get out of my system. Please enjoy this series of increasingly absurd fun facts that never fail to delight me:

- The saxophone was invented in the early 1840s by Adolphe Sax. So it really just is a "Sax-o-phone." For some reason I always thought it'd be deeper than that.

- But Sax didn't stop at his phone: he also graced us with his saxhorn, saxtuba, and—who could forget?—the dulcet saxotromba. Also, this thing:

"Six-valved trombone by Adolphe Sax," as photographed by Wikipedia user Rama, Cc-by-sa-2.0-fr

- But those pitiful horns could only deafen a man at close range. Sax had greater ambitions: his "Saxtonnerre" (a locomotive-powered… organ?) was designed to be heard all across Paris, without any amplification. (This one never made it past the concept stage.)

- At this point, you might have pigeonholed Sax as a designer of niche instruments. Not so; he was a true renaissance man—when he saw the devastation wrought by prolonged sieges in war, he designed the perfect solution: a cannon so giant that rather than besiege a city, one could simply level the entire city with a single shot. He called it—all together now!—the "Saxocannon." Mercifully, it was never built.6

Even by my loose standards, that's a signficant digression. How's the actual album this week?

It's a hoot and a holler! And a times a screech, and also occasionally a… plaintive whine? Point is, there's lots of sounds coming out of the saxophones, including a bunch that I wasn't expecting and a few that frankly I don't associate with competent saxophonists. And yet somehow, it all works? I mean, just listen to this snippet from the end of "Lover Man":

You cannot tell me in good faith that no saxophones were hurt in the making of this album. But you also cannot tell me that their pain was in vain.

Favourite track: All the Things You Are

Week 13: At Newport '63

Enough of this American jazz hegemony! Martial Solal, "an Algerian-born Frenchman who plays more like an American than perhaps any other foreigner,"7 is here to show us a European take on jazz.

This album comes to us (mostly) live from the storied Newport Jazz Festival—charmingly, the back of the album explains that since the only festival slot available for Solal was too short for a full album, they pre-emptively recorded a rehearsal sequence and slapped the festival applause onto the end of those tracks "to make for more natural home listening." (Once you hear the same crowd whistling on half the tracks, you can't unhear it.)

Solal covers some well-trod standards in his set (e.g., "'Round Midnight", "Boplicity"), but the one that really caught my attention was an original composition of his: "Suite pour une frise." Don't be alarmed if the title makes no sense to you; as Martial himself put it: "If you don't understand French, I will make George Avakian to translate in the album notes." Avakian comes through, explaining that the piece is "inspired by an actual frieze; not a classical Greek one but a modern one painted on aluminum high on a modern glass-walled building in Brussels." I, however, needed things broken down even further; I had a vague recollection that a frieze is some architectural thing, but Wikipedia's definition—"even when neither columns nor pilasters are expressed, on an astylar wall it lies upon the architrave ('main beam') and is capped by the moldings of the cornice"8—left me with more questions than answers.

Allow me to spare you my confusion: if a building has a flat part above some columns, and especially if the flat part has a nice design on it, that's a frieze, more or less. Of course, the natural follow-up question is: can we locate the exact frieze that so inspired Solal? Well, the French Wikipedia page for the song mentions that it was commissioned for the inauguration of a frieze by Ralph Cleeremans (which demonstrated Cleeremans' novel "aluchromie" technique that allowed fixing pigment to aluminum). I was able to track down some general information about Cleeremans' work, and while I'm doubtful it's the exact frieze in question, you can purchase one of his originals for a cool 4000 Euros.

But, ah, back to the song itself: "Suite pour une frise" leaps out of the gates with forceful energy, and it builds tension early on that keeps you on the edge of your seat. There's a couple great sections where the bass takes the spotlight, but above all else, this one puts Solal's virtuosity front and centre. For me, that last ingredient is the key piece here—I deeply love the piano, but spartan jazz melodies on the keys just don't seem to grab me as much as they might on say, a saxophone. I'm a firm believer that if you can't play the prettiest notes, you ought to at least play the most notes, and on that metric, Solal does not disappoint. (Mind you, I'm not saying that the piano is inherently less musical than other instruments, as my wife would have you believe—a mournful Chopin is equally moving as a crooning sax, but I've yet to find the former properly represented in jazz.)

One final note: I love how much humanity a live recording captures. Yes, Solal's rhythms and melodies will continue to bounce around in my head, but so will his charming introductions ("…and now, Thelonious Monk's classique de jazz, 'Round Midnight"). I'm sure that to Solal, those off-hand remarks were an utterly forgettable part of the show, but on this album they can't help but colour the listener's overall perceptions—an unintended improvisation, recorded for posterity.

Favourite track: Suite pour une frise

Week 14: Two of a Mind

After last week's saxophone detox, this week the jazz gods smiled upon me with a double helping. And after fourteen weeks, dare I say we're… learning? Check this out: this week's album features Paul Desmond and Gerry Mulligan. We know Desmond from Time Out—in fact, he composed "Take Five."9 Mulligan, on the other hand, enjoyed inspired collaborations with Chet Baker (though sadly Chet is Back! isn't one such example). What's more, the format of this album (two cooperating saxmen with a stereo channel apiece10) calls to mind Sonny Meets Hawk! from a couple of weeks ago.

My overall impression of Two of a Mind is that it's witty; several of these tracks are full of tongue-in-cheek "gotchas" (which, admittedly, are lost on me). Per Avakian's notes on the back of the album, "they will let you hear just enough of what you might expect to let you know that they know that you know—and then they're off on a wholly fresh idea." Clever, but Desmond & Mulligan haven't made a fool of me—I'm too ignorant to be hoodwinked by their tricks. What's more, the title track is apparently meant to be another oblique musical reference for the true devotees. (Spoiler alert: the answer is front and centre on the album's Wikipedia page.)

That same wit shines through in the track names. Apparently, after hearing the rapid tempo on track 4, one of the audio engineers aptly suggested the title "Flight of the Bumblebee." Judy Holliday (an actress who was hanging out in the control room and would go on to marry Mulligan a year after this recording) retorted "or… Blight of the Fumblebee!"11 Now that is an A+ Spoonerism; a brilliant example of the comedic arts that we seek to advance here at the Simpsonian. Desmond was also known to partake himself: a lifelong womanizer, upon crossing paths with a former girlfriend he remarked "There she goes—not with a whim but a banker" (a Spooneristic allusion recalling Eliot's most famous stanza12).

As for the music itself, it's casual, friendly, and coordinated. Desmond's alto contrasts nicely with Mulligan's baritone; their counterpoint is on point.13 The electric guitar on "Untitled Blues Waltz" really got me too—there's an instrument that's been in short supply so far, so the extra funk it brings hits all the harder. Even so, I found myself longing for some of the rougher edges from Sonny Meets Hawk!. I can't quite put my finger on why: the best analogy I have is that Two of a Mind is a wonderfully blended Scotch—Desmond's own favoured Dewar's, perhaps—while Sonny Meets Hawk! is my beloved Laphroaig. Many people in many circumstances will prefer the smooth refinement of the former—but sometimes you want a bare-knuckled peat punch just to remind yourself that you're alive.

Favourite track: Untitled Blues Waltz

Week 15: Together Again!

Going into middle school, I needed to pick an instrument for music class. The choice was clear: I could barely get a whimper out of a flute, and my buzzing on the brass was no good, but by God could I wail on the saxophone. My father was only too happy to indulge my affinity for woodwind by purchasing me a… clarinet. Practicality ruled the day: a clarinet, you see, is significantly cheaper than a saxophone, and is just compact enough to be crammed into one's backpack for easy transportation—my father had no sympathy for the fact that I idolized sexy sax man, not Squidward. I've been unpacking that trauma ever since.

It was surprising to me, then, to learn that all of that unpleasantness could have been avoided had someone simply played me this album all those years ago. Goodman is front and centre on the ol' licorice stick, and blows as hard as any another cat on the scene; there's no shortage of sax appeal here. As for the rest of the quartet: there's no bass (sad), but instead we've got double percussion—drums and vibraphone (!)—to lay down a backbone, plus keys to fill everything out.

From the instrumentation alone, this one struck me as antiquated: nothing else we've heard so far emphasizes these particular instruments, and I can't help but find the combination slightly cheesy. Not in a bad way! It's always fun, and it does legitimately go hard, but clarinet and vibraphone sound so wholesome to me; overall it doesn't quite have the same edge as some other things we've listened to.

Am I right in deeming this sound "dated?" Sort of: Goodman's quartet first made it big around 1936, but this particular recording is an attempt to recapture that magic in 1964 (well after the group had split—hence the "again" in Together Again!).14 Music had changed much in those intervening decades, thanks in no small part to Goodman himself: many consider his 1938 Carnegie Hall concert to be the event that elevated jazz from popular frippery to serious art music. Society had changed as well, and Goodman was involved there too—his racially integrated quartet was highly controversial and nearly unprecedented, but that didn't stop them from touring the South; by all accounts that I've read, Goodman unflinchingly insisted on the equal treatment of all band members at every stop along the way.

I'm not sure what the original reception to this album was in 1964, but I wouldn't be surprised if it mirrored my own: it's lovely music, but also clearly from another time—a long-lost treasure unearthed from a forgotten time capsule. I suppose that's a reputation one only earns by doing something groundbreaking in the first place.

One final thought: while listening to this album, I kept feeling there was some kind of connection I couldn't quite place. By the end of the week I finally pieced it together: the theme from Monsters, Inc. sounds like it could've come right out of a Goodman ensemble (albeit with soprano sax filling in for clarinet). And man, what a bop that theme is.

Favourite track: Dearest

Week 16: It's Uptown

Inside George Benson there are two wolves:

- the coolest cat you've ever seen, and

- the softest, most wholesome guy you've ever met.

In "Clockwise" he's laying down a lick on his electric guitar in tandem with the baritone sax, and hoo boy is it tasty. By contrast, "A Foggy Day" is a cover of a Gershwin song originally made popular by Fred Astaire—Benson's up-tempo take on it injects some much-needed pep, but that doesn't make it any less old-timey.

Many of the artists we've heard so far have been singular students of jazz, devoting their entire career to discovering and mapping her many details. Not so with Benson—there's no disputing his jazz bona fides (as evidenced by this album), but he also extensively recorded pop and R&B;15 many of the 10 (!) Grammys he's won come from those latter two genres. The aforementioned Cool Guy/Nice Guy dichotomy is present in his pop stuff too: in "Give Me The Night" he's about to sweep your girl off her feet and rollerskate16 her away into the Californian sunset, but in "Never Give Up on a Good Thing," relationship counselor Benson exhorts you to… never break up? (This is somewhat less surprising after learning that Benson is a Jehovah's Witness and is celebrating sixty years of marriage in 2025.)

But back to It's Uptown: this is the first album we've heard that makes the guitar the star of the show. I have mixed feelings about that—it's hard to top the cool factor of a well-placed guitar riff, but I also find that the instrument struggles to evoke a certain mournful or plaintive tone that is so often core to jazz. That being said, the trusty six-string has other tricks up its sleeve. A great example is "Bullfight," where Benson starts by setting up a Latin beat with some dense, choppy rhythmic chords, then effortlessly transitions to the solo melody. Finally, it bears mentioning that although Benson came to fame as a prodigious guitarist, he's a great vocalist as well—I find the lyrics of the selections on this album a bit cheesy, but I'm a fan of the clear, bright tone of his voice.

So until next week, follow Benson's example: be the baddest dude you can while still being a good guy.

Favourite track: Clockwise

Week 17: Nina Simone Sings the Blues

Perhaps more than any other artist we've heard thus far, Nina Simone defies categorization. Do we set her against the other female vocalists we've heard? On this album she sings the blues—ought we compare her to Louis? But of course, she was also a talented pianist, and we've heard a few of those as well; maybe they're a better fit?

The answer, of course, is obvious: any attempt to confine such a singular artist to a particular label is an exercise in futility. Simone's own description of her work was "black classical music […] It's a combination of gospel, pop, love songs, political songs, so it is black-oriented classical music, that's what it is." I wasn't aware of how deep her classical music training ran—Simone loved Bach in particular, and that influence isn't hard to hear in this fugal interlude from one of her live performances.

In Nina Simone Sings the Blues, we only get a small slice of her oeuvre (lacking many of her best-known songs), but it's a worthy one nonetheless. This week, let me take you through my favourite tracks from the album.

Buck

This song isn't even two minutes long, but Simone still manages to pack a lot in. The flirty lyrics and light-hearted, breezy vocals make it a fun listen, but my favourite part is the opening organ riff that forms the backbone of the song: it's such a groovy saunter down the keys, and a total earworm.

I Want a Little Sugar in My Bowl

If "Buck" was suggestive, this one is downright filthy—the lyrics aren't subtle in their innuendo, which is especially surprising given that they're heavily based on a 1931 song. (Not a time I associate with free expression of feminine libido!)

This track puts the spotlight on Simone's vocals, and allows her softer side to shine. Simone had an incredible ability to channel powerful emotions (as we'll soon encounter), but this song shows she could be just as effective in a more subdued setting.

Backlash Blues

Here we arrive at a portrait of Nina the activist: a series of horrific murders in the 1960s spurred her to political advocacy; this song, with lyrics penned by her poet friend Langston Hughes is one such example. The protest here is an icy cool, not a fiery rage—the guitar runs are gripping, and the whole piece drips with discontent (though not disempowerment).

The House of the Rising Sun

Surely you've heard The Animals' version of this folk classic. That's not the only time they crossed paths with Simone—their cover of Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood was far more successful than Simone's original recording (which allegedly led to some tensions).

I find Simone's take here jauntier and less haunting than The Animals'—overall I prefer the latter, but the bluesy roots come through more strongly in Simone's.

My Man's Gone Now

Far and away my favourite song of the album: every time I listen, it gives me full-body chills. I can't adequately describe this one—you'll need to listen for yourself—but the album notes give a good taste:

My Man's Gone Now was the last selection taped at the recording session. Miss Simone was physically and emotionally exhausted from previous recording, but she sat down at the piano and began to play and sing this moving "Porgy and Bess"17 tune. The bass picked it up. From somewhere she called up the stamina to deliver with even more intensity and spirit a rare, perfect performance in one take, which could not possibly be improved.

Simone's life wasn't an easy one: her famous temper repeatedly got her into serious trouble; near the end of her life that volatility was formalized in a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. In so many ways, she contained multitudes: despite our inclinations, her music and legacy defy tidy summarization. I'm very glad to have begun discovering her story this week.

Favourite track: My Man's Gone Now

Week 18: Piano Starts Here

Editor's note: we sincerely apologize for the disruption in our usual weekly publication schedule. We recently welcomed a new staff member at the Simpsonian and are very busy training him—we're confident that he'll one day become a valued addition to the team, especially once he can feed, bathe, and clothe himself.

If someone says, "you have to listen to this," and the recording begins with a staticy hiss (as this one does), how should you react? In my opinion, you should be elated. Think of it this way: in 2025, we enjoy a surfeit of extremely high-quality audio recordings; if you want to hear a world-class pianist performing in optimal studio conditions, they're not in short supply. So if, despite that, someone recommends a low-quality recording, there must be something very special about the content. Piano Starts Here falls squarely into that camp.

Unfortunately I lack the time to dive deep into Tatum's life, so I'll confine myself to the basics: he plays like a man possessed, which you can confirm for yourself by listening to thirty seconds of his music. Many regard him as the greatest jazz pianist ever to have lived; many renowned pianists cite him as a formative influence. But what's more impressive to me is his legacy as an anti-influence: Wikipedia has a paragraph on all the musicians who heard Tatum play and found the skill gap so disheartening they gave up the piano entirely. One such flunky was Les Paul, so arguably Art Tatum invented the electric guitar?

Tatum's playing reminds me of only one other pianist: Vladimir Horowitz. Horowitz holds a special place in my heart because I stumbled upon him by pure chance: I purchased a used album of his from my local library on a whim and had my socks thoroughly knocked off the first time I listened to it. The best simile I can offer is that Horowitz's playing (especially in the upper register on the right hand) is like water pouring from a handcrafted teapot: a flow so steady, swift, and perfect that there's no telling where one note ends and the next begins. Tatum is the only other pianist I've heard who can match that lofty bar, and as it so happens, the two were contemporaries; I was delighted to read about some of their encounters here.

Favourite track: St. Louis Blues18

Week 19: Concert by the Sea

Wow, what a contrast with last week. Whereas Tatum astonishes with technical wizardry, Erroll Garner shows that less can be more; Tatum bowls the listener over with an incessant acoustic assault, while Garner makes the silences work just as hard as the notes themselves. By far my favourite feature of Garner's playing is when he really unleashes that booming, thundering bass from his left hand (like in "How Could You Do a Thing Like That to Me"). It feels almost sacrilegious to say, but I far prefer Garner's approach: I will forever be in awe of what Tatum could do on the keys, but Garner strikes me as simply more musical in the end.

That we even have this album is a happy accident: per Wikipedia, there were no plans to record it, but Garner's manager spied a tape recorder running backstage (placed by an enterprising taper); that tape eventually became this album. It was an especially fortunate happenstance for Garner's label, Columbia—the notes for the 2015 rerelease claim that the album brought in over a million dollars in sales by 1958 (three years after the original release). Not bad for a record with an out-of-tune piano and barely audible backing instruments!

As is tradition around here, allow me to offer a connection in closing: early on, we met Art Blakey, along with his Messengers. Blakey's widely considered to be one of the greatest jazz drummers of all time, and to some extent he has Garner to thank for that: according to Blakey, he started his career gigging on the piano, but that ended abruptly one night when the club owner ordered him onto the drums instead. One gets the impression that Blakey perhaps wasn't entirely enthusiastic about the request at first—but when the club owner pulled his pistol on Blakey, Blakey had a sudden change of heart. For whom was Blakey vacating the piano bench? You've already guessed it, of course: Erroll Garner.

Favourite track: Mambo Carmel19

Week 20: Head Hunters

What the funk is this‽

Right from the first listen, this has jumped into my personal top five albums from this project, and probably the top three. It's a total mind virus; I've been listening to it every day since. Once you have the opening lick in your eardrums, it's all over. There is simply no escaping it.

I don't have any particularly intelligent analysis (as usual); all there is to say is that the vibes here are immaculate. "Chameleon" makes me want to stalk around Manhattan at 2 a.m. "Watermelon Man" makes me want to drive around like that old 3D Gorillaz game (video). "Sly" makes me want to frantically scramble to evade the police. "Vein Melter" makes me want to… actually I'm not sure; that one's pretty chill.

I had never heard of Hancock before this, which is impressive, given that he's accomplished pretty much everything there is for a musician to accomplish. A quick sampler of some of his laurels: personally scouted by Miles Davis for his "Second Great Quintet;" 14 Grammys (including Album of the Year); and an Oscar for Best Original Score. No lack of commercial success either: Wikipedia claims (albeit without citation) that Head Hunters was the best-selling jazz album ever until Breezin' (by George Benson) came along. Plus, he made a nice chunk of change recording jingles for all kinds of TV commercials, and he composed the theme for a Fat Albert special. But he isn't a commercial sellout either: Hancock was (and continues to be) chairman of the "Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz" for so long that they decided to just rename it the "Herbie Hancock Institute of Jazz" instead.20

This album is arguably our first glimpse into jazz fusion: the extended solos and general structure are reminiscent of the jazz we've heard so far, but the instrumentation (especially the heavy focus on synthesizers/electric piano) and general funkiness are a new twist, and I am 100% here for it. And can I just say: fusion anything is obviously always going to be better than the original. It's practically so by definition—take the best parts of multiple things and stick them together—how could that not be better than what you started with? French fries in my falafel wrap? Synthesizers in my jazz? Yep, a double helping of each please. FUSE IT!

Favourite track: Chameleon

Week 21: The Best of Two Worlds

Ah, we've arrived at bossa nova: Spanish for "the new boss," because when João Gilberto and Stan Getz popularized the genre with their 1964 album Getz/Gilberto, everyone took notice of the new boss in town. Or something like that.

This album, The Best of Two Worlds, is the reunion of Getz (saxophone) and Gilberto (vocals) over a decade later. (Gilberto's then-wife, known professionally as Miúcha, joins as well, providing the English vocals.) This music is precious: it's exquisitely beautiful, and sumptuously smooth. That smoothness is pleasing, but at times it runs the risk of becoming sedate. When I listen to jazz, I'm not looking to appreciate an abstract Rothko with detached amusement—I want my passions inflamed, dammit! Tijuana Moods is such an interesting contrast here: both albums have their souls in Latin America, but their vibes could not be any more different. The Best of Two Worlds is foolproof dinner party background music; with Mingus it's chaos and confusion, fire and brimstone. (Yes, the hellfire is a good thing.)

That being said, the first two songs on this album are sublime enough to transcend my impertinent grousing. "Double Rainbow" is the most magnificent song ever to feature a double rainbow, and that is a category with stiff competition. But "Aguas de Março (Waters of March)" is the runaway star for me. I don't generally go for its style of free-form, abstract lyrics, but here everything just works, thanks largely to Miúcha's lithe vocals and Getz's legendary tone. (No shade to Gilberto, who is a great singer as well, but he just doesn't make my heart ache like Miúcha.) Apparently the lyrics are inspired by the sudden, heavy March rains in Rio de Janeiro, which routinely carry various detritus through the streets. It's a highly evocative image, and one that makes me think I need to get outside more. I shudder to think of a version of this song inspired by my life… A bit, a byte, a keystroke at night…

Favourite track: Aguas de Março (Waters of March)

Week 22: Jaco Pastorius

I expected to like Jaco Pastorius—both the bassist as well as his self-titled debut album—from the start. It is the official editorial position of the Simpsonian that Rush is the greatest rock group of all time, so I hope there is no doubt when I say that I surely appreciate a proper bass-slapping. Alas, despite all that, my first listen of this album sailed right under my whelms. I had a hard time following along or categorizing the album: we start with the virtuosic but minimal "Donna Lee," followed by the distinctly R&B "Come On, Come Over", then a few progressive tracks, finally tied up with some soaring strings?21 I couldn't make heads or tails of it.

But with repeated listens, something finally clicked. The real "a-ha" moment for me was likening this album to Daft Punk's Random Access Memories—bear with me. Yes, the two albums sound pretty different, but they both explore all kinds of different musical ideas/genres, while still maintaining a coherent, singular identity that binds all the tracks together. Even when drilling down to the level of individual tracks there's some fun parallels; let me break them down for you:

| Archetype | Jaco Pastorius | Random Access Memories |

|---|---|---|

| Catchy dance hit featuring another R&B group on vocals | "Come On, Come Over" (feat. Sam & Dave) | "Get Lucky" (feat. Pharrell Williams) |

| Minimal track that strongly features a single instrument | "Portrait of Tracy" (maybe "Donna Lee" as well?) | "Within" |

| Soaring string introduction | "Forgotten Love" | "Beyond" |

| Eight-ish minutes of experimental prog something | "Kuru / Speak Like a Child"22 | "Touch" (arguably "Giorgio by Moroder" too) |

But there's also a more direct jazz connection worth pointing out here: Herbie Hancock! We first met Hancock a couple weeks ago alongside his Headhunters; Hancock features prominently on this album too. He plays keyboard on several tracks here, and the "Speak Like a Child" half of "Kuru / Speak Like a Child" comes from an earlier composition of his. Hancock was clearly a fan of the young Pastorius; the back of the album features this extended praise:

Jaco is a phenomenon. He is able to make sounds on the bass that are a total surprise to the sensibilities. Not only single notes, but chords, harmonics, and all sorts of nuances with the color of the instrument that when combined and translated through Jaco make for some of the best music that I've heard in a long time.

Of course, it's not the technique that makes the music; it's the sensitivity of the musician and his ability to be able to fuse his life with the rhythm of the times. This is the essence of music. On this record Jaco captures some of that rhythm.

So after a week's worth of listening, I've ended up exactly where I thought I would: this album is awesome; highly recommended.

Favourite track: Kuru / Speak Like a Child

Week 23: Heavy Weather

We're back in jazz fusion land, with a fun chain of connections leading to this week's album: we first started getting funky with Herbie Hancock, who was also instrumental in Jaco Pastorius's debut album. Jaco is back again this week as the sole bassist for this Weather Report album—a gig he secured by approaching the band's leader, Joe Zawinul, after a show and proclaiming "I'm John Francis Pastorius III. I'm the greatest bass player in the world." ("As was [Jaco's] habit," Wikipedia adds!) Jaco's debut album was great, but this is the one that made me a believer: in my listening notes, I wrote "the electric guitar is the star of this album". So imagine my surprise when I discovered there is no electric guitar on this album—it's just Jaco doing Jaco things on his bass.

The liberal use of synthesizers gives Heavy Weather a full and more modern sound compared to many of the other albums we've heard—and with Pastorius on the bass, it should come as no surprise that he gets plenty of time in the spotlight (especially on "Teen Town"). The many solos throughout the album (bass and otherwise) continually enthrall (e.g., the electric piano (?) near the end of "A Remark You Made"; the sax at 2:00 in "The Juggler"), but so too do the smaller ornamentations—the "da-ding" on the piano at around 1:08 in "The Juggler" is tiny but adds so much. "Rumba Mamá" feels like the odd one out to me here: recorded live in 1976, it's heavy on vocals and Latin beats, but light on everything else—a significant departure from the rest of the album.

The best-known song from the album is "Birdland," and while it's a phenomenal track (especially Jaco's bass near the start!), my one critique is that it ends up feeling a little too "sunshine & rainbows" for me. There's so much intrigue and anticipation at first, but I find the theme introduced right at 2:00 so irrepressibly upbeat that it dominates the mood, and collapses any emotional ambiguity into a one-note feelin' good. If you're looking for an easy smile, it's great; I only wish they had left a little more of that initial edge on it. But that depressive nitpicking of an irredeemable curmudgeon hardly dampens the bright skies on display here—I'll be returning to Heavy Weather season after season.

Favourite track: A Remark You Made

Week 24: Marsalis Standard Time, Volume 1

Over the past several weeks, we've seen a certain correlation: the more recent an album is, the more it seems to depart from "traditional" jazz, in favour of pushing the boundaries or incorporating other genres. Marsalis Standard Time, Volume 1 bucks that trend: despite being first released in 1987 (a mere 38 years ago…), there's no bells and whistles here, nor is there even a hint of fusion: this is just old-school jazz, baby.

What I didn't know during my first listen is that this approach is very characteristic of Marsalis. He's a staunch traditionalist in the world of jazz, a proponent of "straight-ahead" jazz. Accordingly, on this album Marsalis picks a number of standards and brings them to us with exacting precision. In other weeks, we've heard original compositions that are clearly the works of an auteur intent on moving the art as a whole forward; by contrast, Marsalis is content to simply add his take on tried-and-true tunes. For me, the result is more reminiscent of classical music than anything else: the compositions themselves are taken to be fixed, and we instead are interested in a performer's personal interpretation of them.23 And just like classical music, the contemporary listener benefits from advances in recording technology; the tracks here are crisp and clear, unlike some of the earlier albums we've heard. Overall, Marsalis and his band produce wonderful results here, and I think there is value in some musicians focusing on excellent performances of "no-nonsense" works. But I can't endorse his philosophy as a whole—in a world with only Marsalians, wouldn't jazz become a dog chasing its tail, celebrating where it's been without having anywhere to go?

But let's set ideological quarrels aside, because this week we've got just enough contenders for our first-ever… Standards Showdown! Part of the culture and tradition of jazz is a shared songbook of "standards" that are routinely covered by performers. After 24 albums, we've got enough overlap that I thought it would be fun to put Marsalis's recordings head-to-head against some others.

"April in Paris" vs. Garner

I'll be honest: when I first listened to these side-by-side, I couldn't tell they were supposed to be based on the same tune. After comparing to some other recordings, it seems to me that Garner was pretty liberal with his ornamentation. Not that he's the first to do so, mind you—Count Basie's Orchestra smuggled "Pop! Goes the Weasel" into their cover?? To my ear, Marsalis is truer to the heart of the tune, and for that, he takes the first point.

Note: "April in Paris" was also on the Helen Merrill album we heard, but since she sings hers, I'll exclude it in the interest of trying to keep an apples-to-apples comparison.

Winner: Marsalis

"[A] Foggy Day" vs. Benson

No disrespect to any of the great crooners, but I've always preferred the energy of Benson's up-tempo, snappy take on this one. However, I can't help but find the lyrics themselves so cheesy.24 Marsalis, by contrast, get to have his cake and eat it too: he takes that earworm melody and spins it out instrumentally for a full seven-and-a-half minutes. All the fun, with none of the cheese—notch a second point for Marsalis. (It's an especially meaningful win for Marsalis, because Benson was one of the poster boys for the "corruption" of jazz, with his pop stylings.)

Winner: Marsalis

"Autumn Leaves" vs. Garner

I am a sucker for the drama with which Garner suffuses this one: when that left hand comes crashing in like the waves against the shore at his Concert by the Sea, it gets me every time. While I do love the tug-of-war between the fast and slow tempi at the start of Marsalis's take, it never reaches the same emotional highs for me. Garner wins the rematch, preventing a Marsalis sweep!

Winner: Garner

Two out of three ain't bad, Marsalis—a solid showing indeed for the inaugural Standards Showdown. A couple final tidbits of trivia to close us out:

- Marsalis is an alum of The Jazz Messengers—and that's not the first time we've seen a connection to Art Blakey's group.

- Marsalis is one of the only artists we've heard who is still actively performing. In fact, he's currently on tour.

Favourite track: Caravan

Week 25: Bird: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack

Two weeks ago, we were listening to "Birdland" by Weather Report, and this week we come full circle: that song took its name from a New York jazz club, which was itself named after Charlie "Yardbird" Parker—better known as just "Bird." Parker was one of the most influential saxophonists in the history of jazz, and is the subject of Clint Eastwood's 1988 biographical film Bird, from which we get this week's album.

Eastwood is a lifelong lover of jazz for whom Parker was a particular inspiration. So when he set out to tell Bird's story, he faced a problem: given Bird's untimely passing, the recordings we have of him are generally of poor quality, and would have stuck out sorely in the movie. Eastwood and music supervisor Lennie Niehaus agreed that having a contemporary saxophonist "dub" Parker's iconic playing would be sacrilegious, so they tasked the audio engineers with surgically extracting Parker's solos from those original recordings (!).25 Contemporary musicians then re-recorded the other parts alongside those authentic Parker solos for the film's score.

As part of this week's research, it only seemed right that I supplement the soundtrack by watching the movie. It's over two and a half hours long, but it never seemed to drag for me, owing largely to the warmth, humour, and almost childish tenderness Forest Whitaker brings to the lead role. In my viewing, two things stood out in particular: first, it was fascinating to be visually immersed in the jazz culture of 1950s New York City. Throughout this project, our exposure to the leading names of jazz has been almost exclusively through their musical output—Eastwood's biopic delivers the sights and social dramas of the period in addition to the music. And while the NYC of today in many ways looks quite different compared to that depicted in Bird, one scene hasn't changed: wherever jazz thrives, there will be bustling clubs filled with drink-laden tables and packed with an audience enraptured by the cats on stage.

Secondly, it was fascinating to be reminded of just how controversial bebop was in its nascent days—after Bird and the gang try to bring this new style to the West Coast, their engagement is cancelled early, with some unnamed music executive declaring "bebop tends to pervert young minds." Hoo boy! In our era of drill music, and, well, WAP, it's quaint to see how reviled bebop was for its… use of chromatic scales? (Yes, okay, presumably much of that ill reputation was due to bebop's association with the drug scene—that same drug scene that killed Bird before 35, along with a slew of other jazzmen—but still, perverting young minds??)

But for all these words I have yet to comment on the music itself. Alas, I clearly have yet to achieve jazz transcendence: for all my efforts, I can't quite detect what makes Parker so singularly spectacular. That's not to say I didn't enjoy it—"Lester Leaps In" has infectious energy; "Laura" is heart-wrenching; "April in Paris" might've won last week's Standards Showdown —but what most caught my ear were Jon Faddis's fleet-fingered trumpet solos on "Ko Ko" and "Ornithology" (where he covers his mentor, Dizzy Gillespie).

Let me close this week by once again lamenting the devastating effect that heroin had on Harlem and jazz, aptly chronicled by Stephen Eide in this piece. That is only one of innumerably many examples of communities ravaged by drugs, but it is one that robbed us of so many musical visionaries at their peak. Though Charlie Parker was taken from us far too soon, he is not forgotten—Bird lives.

Favourite track: Ornithology

Week 26: Ellington Uptown

In an attempt to remedy last week's bebop perversion of young minds, this week brings a double helping of wholesome jazz—straight from one of America's most beloved band leaders, Duke Ellington. The last time we heard from the Duke, he was going head-to-head with Count Basie; this week his band has the stage to themselves.

Ellington Uptown was first recorded in late 1951, amidst a somewhat difficult time for Ellington: his signature big band style was long past its commercial heyday, and several key members of his band departed earlier that year (most notably Johnny Hodges). Meanwhile, one of Ellington's main creative ambitions was to move jazz beyond the three-minute compositions that had originally brought him fame and success. Those forces all coalesce here, and the result is our most symphonic album yet: multiple tracks (especially "A Tone Parallel to Harlem", "The Controversial Suite", and "The Liberian Suite") are extended compositions, featuring semi-formal structures more reminiscent of classical music than of traditional jazz. (There's even strings!) Might this be a precursor to what would later be dubbed "Third Stream?"

I really enjoyed listening to Ellington Uptown, and this week I'd like to comment on some of the individual tracks in more detail. We begin with "Skin Deep," and what a way it is to start! This one grabs your attention from the first note and never lets go. This is also the album's biggest dose of percussion—I haven't measured it exactly, but I'm pretty sure that fully half of this song's 6:49 runtime is just drum solos.

"The Mooche" is slinking and sly; it makes me want to strut around once again in Grim Fandango's Rubacava. There's plenty of solos to go around here, from clarinet to saxophone, but most remarkable is the rumbling wah-wahs from the trombone. (Wikipedia mentions that Tricky Sam Nanton, a long-time member of Ellington's band, was one of the pioneers of that distinctive wah-wah sound, though sadly he passed away before this album's recording.) Side note: I assumed that the titular "mooche" was meant to evoke the French mouche, but apparently Ellington just meant someone who's always borrowing off of you—y'know, a mooch—which is sometimes how the title gets spelled. Oh, how I love a side of orthographic pedantry to complement my jazz.

'Take the "A" Train' is the only track I'm mixed on. I first fell in love with that tune—an Ellington standard—in the band battle version with Basie; in my opinion, that recording still has more raw energy. The Ellington Uptown version adds some vocals (including scatting) that I could take or leave, but doubling the track length to eight minutes gives them more liberty to explore and experiment, which is fun.

"A Tone Parallel to Harlem" captures the quotidian routines of a community, from the bustle and excitement of dancing in the street, to quiet, reflective evenings in the park. Wikipedia cites a favourable comparison to Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue, which I find quite apt. Listen carefully to the trumpet voice at the very beginning, which plaintively welcomes you to "Haaar-lem."

Of the two Controversial Suite tracks, "Later" is the one that sticks with me, owing to its distinctive "tick-tock" pulse throughout. I need a mod to make it the background music for a certain Mario Kart course…

Finally, in the Liberian Suite, I love the sax solo at the end of Dance No. 1, as well as the strings in Dance No. 3, but the vocals in "I Like the Sunrise" are the real show-stopper for me. The lyrics are simple, but the melody is so moving, and delivered with such confidence, that I'm enthralled every time. This was commissioned by the government of Liberia to celebrate their centennial—I wonder if it's still known there.

So there you have it: nearly 80 minutes total (in this extended CD re-release) and I like it all. Perhaps this makes me unhip, but I have a real soft spot for big band: not to pooh-pooh the bebop virtuosos, but by dint of sheer numbers, big bands offer a fullness and richness that no small ensemble can equal. Couple that with some pointers on structure and instrumentation from the classical world—without any of the possibly attendant stodginess—and you've got a recipe for some great tunes.

Favourite track: The Mooch(e)

Week 27: Jazz Goes to College

Jazz Goes to College‽ As a card-carrying pseudo-intellectual, this title has me salivating: I can't credibly claim to have jazz in my soul, but perhaps Brubeck and his quartet have distilled jazz's inscrutable mystique into pure mathematical equations; at last, unquestionable hipness might be within reach for any square willing and able to bring their intellect to bear upon the subject.

…but alas, the title is rather more literal than that: this album is a compilation of live sessions recorded at several universities across the Midwest. Time Out, also by Dave Brubeck Quartet, is one of my absolute favourite albums from the first half of our experiment, so I came into this week with high hopes. I leave the week… disappointed, but only very slightly so.

You see, what most captured my imagination in Time Out was the album's signature rhythmic experimentations, most notably in "Blue Rondo à la Turk," which tumbles along with the frenetic insistence of a toddler who has just learned to walk—every step has their entire momentum behind it; looking on, one is amazed that either avoids faceplanting. Jazz Goes to College (recorded five years before Time Out) doesn't feature similar innovations. What it does offer, however, is a fine selection of very cool jazz. I've previously written that I'm more partial to the up-tempo, fiery stuff; while I still think that's true in general, this album Bru-bucks that trend. The tracks here are generally relaxed and minimal, with Brubeck and Desmond frequently trading the spotlight, but without ever growing boring or bland. Much of that feat is owed to their musicianship: perhaps I'm deluding myself, but my immediate reaction to first hearing Desmond on this album was recognition. I'd surely fail any comprehensive blind saxophonist identification quiz, but those first phrases immediately called to mind both Time Out as well as Two of a Mind; similarly, Brubeck is quite distinct amongst the many pianists we've heard so far.

As for the tracks themselves: we start off strong with almost 12 minutes of "plain old blues"26 in "Balcony Rock." Desmond's smooth, signature style never disappoints, and it's only heightened by the contrasting tension Brubeck introduces; there's a series of chords that build, swell, and resolve around the 6:45 mark that perfectly encapsulate how a jazz pianist can thrill without invoking the sheer virtuosity of, say, Art Tatum. "Le Souk" is my favourite track—it would be another several years before the quartet served as ambassadors abroad and brought back Turkish rhythms for "Blue Rondo," but the early Middle-Eastern melodic influences evident in "Le Souk" already presage those later explorations. Just like last week, I'm somewhat flat on another cover of "Take the 'A' Train": its iconic, rollicking piano riff has always been at the heart of the song for me; here, that element is downplayed so that Brubeck and the gang can try on some fresh ideas—none of which exceed the original to my ear. In fairness, "Take the 'A' Train" was 15 years old at the time of this recording; I suppose that it would've been decidedly unhip for a cool jazz group to play an ancient standard "straight."

All told, while Jazz Goes to College wasn't the revelation I was hoping for, it's still a laudable lecture from a pre-eminent professor of cool jazz—well worth trekking across campus for, hangovers be damned.

Favourite track: Le Souk

Week 28: Satch Plays Fats: A Tribute to the Immortal Fats Waller

Well, it's week 28 and we've officially come full circle: ol' Pops was the one to kick this whole thing off, and this week he's back once again. Interestingly, that earlier album and this one were contemporaneous releases as well: Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy helped revive public interest in Armstrong in 1954; Satch Plays Fats was the follow-up in 1955. Overall, I prefer Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy: they both feature stellar vocals and trumpeting from Armstrong, alongside great banter with Velma Middleton on several tracks, but the nearly nine-minute-long "St. Louis Blues" on the Handy album is unparalleled, and the whole thing is chock-full with a sheer joy that I don't think has been matched by anything else we've heard.

But beyond that simple comparison, what shall we chew on this week? Regular readers know that there isn't any prescribed structure for a Fifty weeks of jazz entry—perhaps we ought to examine this album's namesake, or the fascinating life of his chief collaborator? Or what about this Avakian fellow, whose name seems to grace every Columbia jazz record; ought we pull back the curtain there? Not to mention the music itself; there's some overlap with a Sarah Vaughan album; perhaps we're due for another Standards Showdown? All good options, but this week I want to zero in on one song in particular: one that hooked me with its intro, but kept me on the line with a linguistic puzzle.

Specifically, my favourite track this week is the lively and flirtatious "All That Meat and No Potatoes." I mentioned earlier that I love the banter between Armstrong and Middleton; this track's got it in spades. But the music's just as fun: Armstrong opens with a wide, bright, jaunty riff that he explores while the background instruments each take a turn joining in on the fun. Unsurprisingly, the chorus the really swings—but, ahem, what does the phrase "all that meat and no potatoes" mean, exactly? I'll give you the first half of the lyrics; see if you can figure it out (below, Armstrong's part is bolded):

Hey Pops! What’s wrong Daddy?

You look like something's botherin’ you

There's nothin’ botherin’ me honey

That a piece of roast beef can’t fix upA man works hard, then comes on home

Expects to find stew with that fine ham bone

He opens the door, then starts to lookin’

Say, woman, what’s this stuff you cookin’?Now all that meat and no potatoes

It just ain’t right, just like green tomatoes

Here I’m waitin’

Palpitatin’

With all that meat and no potatoes

Pencils down—what did you come up with? Of course, we all know the phrase "meat and potatoes," meaning something plain or pedestrian—but that doesn't seem to quite fit here. "All that meat and no potatoes" suggests a certain imbalance, but in the context of 1940s,27 that strikes me as a fortuitous one: surely midst WWII you'd happily take a double serving of meat and forego the potatoes?

The trick to deciphering this one is to understand that every song from the 1930s to the 1950s28 that purports to be about food is actually about sex. Through that lens, we realize that Fats isn't really complaining about his dinner (his nickname matched his figure; he hardly seems the type). Rather, he's lamenting that his otherwise buxom ("all that meat") lady friend sports somewhat underdeveloped bazongas ("and no potatoes!")—the breasts, of course, being the most tuberous aspect of the female physique.

Don't believe me? I don't blame you; it certainly doesn't seem to agree with certain dictionaries of idioms. But whereas other, lesser blogs29 are happy to simply purport this as fact, here at the Simpsonian we pride ourselves on our research, and by research, I mean asking ChatGPT. Spare me your scowl, philistine; yes, upon first asking, ChatGPT simply regurgitated many of the same sources upon which I've just heaped scorn, but—and here's the thing!—you can just ask it for a better source. In the present case, that yielded Green's Dictionary of Slang, which appears to have garnered praise from the academics, in addition to the imprimatur of Oxford University Press (but see also some mild criticism from—where else?—Language Log). Green has a direct hit for our phrase, which confirms the ribald definition, and even offers a further literary citation as evidence. It also offers many other filthy euphemistic uses of the word "meat" (including an application of "all that meat and no potatoes" to the male anatomy), but that's neither here nor there.

Well, that about does it for me this week; I'm stuffed. There's many fine details we haven't the time to discuss (like the "Rhapsody in Blue" quotation in "Ain't Misbehavin’"!), but allow me to steal Mike Judge's conclusion for myself: at the end of Office Space, the flames devouring Initech are stoked by some hot—and strangely familiar—background jazz.30 You guessed it—all that meat and no potatoes!

Favourite track: All That Meat and No Potatoes

Week 29: ’Round About Midnight

We first heard Davis on his best-known album, Kind of Blue; this week, with ’Round About Midnight, we wind back the clock just a few years before that landmark release. Recall that Kind of Blue was a pioneering exercise in "modal jazz;" by contrast, ’Round About Midnight is more transitional: we hear some of Davis' last mainstream work in bebop/hard bop alongside experiments in a "cooler" style that would eventually lead to him advancing the frontiers of jazz.

There's lots to love in this album: for me, Davis & Coltrane generally steal the show (their interplay and tone on "Bye Bye Blackbird"—Coltrane's in particular—are a real highlight), but the rest of this "first great quintet" each has their moments too, like the piano at ~5:45 in "All of You," the bass solos in "Little Melonae," or the drums at the end of Budo (which instantly called Art Blakey to mind for me, though it's actually "Philly Joe" Jones).

Of those many delights, the track that particularly stood out to me on first listen was "Ah-Leu-Cha." "Ah-Leu-Cha" is a Charlie Parker composition;31 we're firmly in bebop territory here (and the lively tempo comes in strong contrast to the relaxed "’Round Midnight" that precedes it). Fascinatingly though, Parker's original recording was noticeably more relaxed than what's on this album—and in at least one live performance, Davis counts the group in on a truly blistering tempo. Listen for yourself (for a simulated K-hole, repeatedly listen to the last one, then immediately drop back down to the first):

- Slow (relatively speaking!): original Parker recording

- Medium: ’Round About Midnight

- Ludicrous speed: Miles & Monk at Newport

- To me, this one is frenetic but not awful; I'm generally Team Faster Is Better. At least one critic disagrees: as Jack Chambers writes on page 288 of his epic biography of Davis: "The sextet's performance is substandard. Davis' most conspicuous contribution comes in tapping out overzealous tempos on all tunes, including a breakneck tempo on Ah-Leu-Cha that reduces the ensemble to shambles."32

- Love it or hate it, this has been on the official Miles Davis YouTube channel for nearly a decade and has hardly 500 views (~1% of which are from me)—that seems wildly low.

(Hat tip to Deep Groove Mono, for breaking down the relevant Ah-Leu-Cha history in this very helpful post.)

Overall, I'm still not sure where to place ’Round About Midnight—in many ways, it feels like an album caught between worlds. If I want nothing but hard bop, I'd sooner reach for The Messengers, and if I really want to cool off, there's no beating Kind of Blue. But if all you're looking for is some great jazz from a formidable quintet, and you're not too picky on subgenres, you could do a lot worse than ’Round About Midnight.

Favourite track: Ah-Leu-Cha

Week 30: The Sound of Jazz

Why is nearly every mass-market, commercially-produced creative work so universally crap? You know the answer—perhaps you've lived it—pointy-haired bosses, sticking their noses where they don't belong, rooting madly for pecuniary truffles to sate the unending appetite of beancounters and shareholders alike—all at the expense of preventing the true visionaries from making something special.

But, rare as they may be, there are yet exceptions. One such shining example took place in 1957, when one uncompromising TV producer (Robert Herridge) somehow convinced CBS to give him creative carte blanche in putting together a live, one-hour jazz concert for TV: The Sound of Jazz.

Look, technically I should be reviewing The Sound of Jazz, the album recorded from the rehearsal for the TV broadcast. And I generally do prefer the precision and perfectionism that can only really be achieved in the studio. But just as poetry is meant to be appreciated as more than words on paper—it only truly comes alive in our voices—so too jazz ought to be more than just sterile, pristine recordings; it should also be shared, performed, celebrated. So if you happen to have a spare hour, I encourage you to tune in to The Sound of Jazz, the TV program, for yourself. Not only will you hear some great jazz, you'll also get to watch some jazz greats not merely performing, but also luxuriating in both the music and the company of each other. Allow me to take you through my favourite vignettes of the broadcast.

Last week, we heard from "Philly Joe" Jones on drums. This week we once again have jazz drummer Jo Jones on percussion, who, somewhat surprisingly, is a completely different guy. (He was sometimes nicknamed "Papa" Jo Jones to distinguish him from the younger Philly—despite the 12-year age difference between Philly and Papa, the shared name seems to have imparted a mortal synchronicity: they died within days of each other in 1985.) As it happens, we've encountered Jo Jones before; remember Charlie Parker's "origin story" of having a cymbal thrown at him during a cutting session gone awry? Yeah, that was Jo Jones. For the life of me, I cannot reconcile that outburst with the happy-go-lucky percussionist featured in The Sound of Jazz. Seriously, how can this grinning goof be the same person who "nearly decapitates" Bird?33

Man, Thelonious Monk sticks out like a sore thumb here. Not just in what he plays—though his avant-garde composition "Blue Monk" forms a notable contrast with the other tracks, which lean more toward blues and swing—but also in how he plays the piano. Compare Basie elegantly tickling the ivories while Billie Holiday hovers at his shoulder, with Monk, who pounds the keys like they owe him money. The cameraman knew how to milk this for maximum drama: check out this shot of Basie watching Monk play (seated directly across from each other) and decide for yourself what Basie's thinking in that moment. (Monk did not take kindly to that stare!)

I hadn't even heard of Giuffre before this, let alone his trio, but their performance of "The Train and the River" is by far my favourite track. Seeing it live only further accentuates the magic: sometimes I find a trio to be a little bare in its sound, but that's not the case here; every time I listen I'm blown away by the depth and richness of texture that they're able to evoke. Note to self: pick up another one of their albums sometime.

But the real star of the show is Holiday herself. That she even appears is a minor miracle: the TV execs awoke in a meddlesome mood the day of the performance, and sent a note to the studio: "we must not put into America's homes, especially on Sunday, someone who's been imprisoned for drug use."34 Herridge informed them that if Billie was through, so were he and the other key staff. The execs relented, and in doing so created the most heart-wrenching moment of the evening. You see, Holiday had a complicated relationship with Lester Young, who was playing saxophone that night: decades before, the two had been frequent collaborators and close friends, but the vicissitudes of time had since pulled them apart. Young was in poor health at this point, and wasn't even expected to stand for his solo—but watch what happens when he gets his moment with Lady Day.